Sadly, David was an exception.

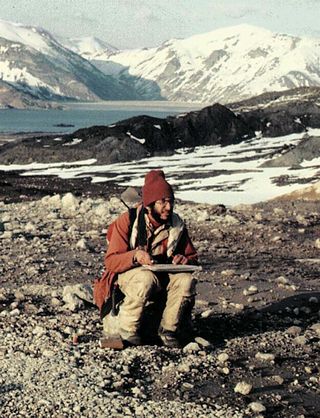

The iconic image of David A. Johnston at Coldwater II.

David completely his undergraduate work in geology at the University of Illinois, and followed up with his master's and doctorate work at the University of Wisconsin. In 1979, the 29-year-old joined the United States Geologic Survey, or USGS. Johnston's specialty was in gas sampling. He hoped it would allow scientists to identify hazards before they violently erupted.

Johnston's work took him across the Pacific Northwest, and he was at his alma mater, the University of Wisconsin, when Mount Saint Helens woke herself from her 123-year rest with a shudder.

The first earthquakes struck on March 15th, 1980. Intrigued, Johnston contacted his mentor, Stephen Malone, who immediately allowed him to escort reporters to the area. Johnston was the first geologist on the scene and remained a leader of the team studying the mountain.

By March 24th, the vulcanologists were confident that the earthquakes were the precursor to an eruption. On the 26th, a phreatic, or steam, eruption burst forth from the mountain.

This phreatic eruption took place on the 30th.

On April 17th, a bulge appeared on the north side of the mountain. Concerns arose that this could become a lateral blast, which is exactly what it sounds like: a blast erupting from the side, and not the top, of a volcano.

This series of photos from Scientific American shows the growth of Mt. St. Helen's "ominous bulge":

It seems surprising in retrospect, but Johnston was one of few people to share this opinion. Though it was obvious the mountain was close to erupting, the questions of where - and when - remained a mystery.

Governor Dixy Lee Ray declared a state of emergency on April 3rd, and by the 30th, a "red zone" was declared around the volcano, allowing only people with a special pass to climb the mountain.

David Johnston takes a sample from the mountain's crater lake, April 30, 1980.

Despite the bulge, which was growing at the rate of 5 to 9 feet per day, the north side of the volcano still wasn't producing much vent activity.

This is a vent, or fumarole.

Wrongly assuming that this meant an eruption was further off than they thought, the USGS instead warned residents about the potentiality of landslides from the north face. Johnston was the one who issued the warning to the press.

By this point, Johnston was downright scared of the volcano. It was ready to pop at any minute. It was incredibly dangerous to be anywhere on the slopes of St. Helens.

And then the volcano went silent.

The phreatic activity slowed. Between May 10th and May 15th, the only change in the mountain was the growth of that looming bulge. On the 16th, the phreatic eruptions stopped completely.

At this time, Johnston was mentoring a student, Harry Glicken.

Harry Glicken

Glicken had been monitoring the Coldwater II station, using laser ranging to track the growth of the bulging mountain. After working six days straight in the tiny trailer, Glicken needed a day off to visit with his professor for his graduate work at the University of California. He was supposed to be relieved by geologist Don Swanson. Swanson, however, wanted to meet with a graduate student who was returning to Germany the next day.

Glicken bumped into Johnston in the hallways of USGS and asked if he would take his place on May 18th.

Johnston was extremely reluctant. He had issued the most forceful warning to the public to stay away from the mountain, and had been scolded by his superiors for it.

"I don't like this at all," a newspaper quotes him as saying. "I'm not trying to be an alarmist, and I'm usually pretty calm around volcanoes, but I'm genuinely afraid of this thing... I think it would be wise to get out of here."

After heavy hesitation, he accepted the job of the post at Coldwater II. It was six miles away from the bulging north face, after all. Surely whatever happened on the mountain wouldn't reach him.

Just before he left, Glicken snapped the photo of his mentor in front of the tiny trailer, notebook in hand, grinning at the camera.

At 8:23am in the morning of May 18th, Mt. Saint Helens erupted.

David must have dove towards the radio. He screamed his last words into the microphone.

"Vancouver, Vancouver, this is it!"

Amateur HAM radio operator Gerry Martin saw the blast as well. He broadcast, "Gentlemen, the uh... camper and the car sitting over to the south of me is covered. It's gonna get me, too. I can't get out of here..."

Then his signal went silent, as well.

A recording does exist of Martin's message, but I can't seem to locate it at this time. Please contact me if you find it!

Robert Landsburg, a local photographer, already had his camera on a tripod. As the mountain burst forth its fury, he pumped out four photos, unwound the film, and threw it into his backpack. He then dove on top of the backpack to protect its contents.

His pictures survived.

Glicken was devastated and guilt-stricken. He convinced three separate helicopter pilots to fly over the mountain, but there was no sign of the trailer or his mentor - they had completely vanished.

Don Swanson found Johnston's parka and backpack.

It wasn't until 1993 that the trailer from Coldwater II was recovered, but the body of David Johnston was never found.

A touching tribute to Johnston and the other scientists who perished that day is located here:

I will admit this: I cry. Every time. Every time I catch sight of the geologist he was, and realize anew what we lost that day, I tear up. He furthered our knowledge; he saved lives by being one of the voices saying that St. Helens was still dangerous even when she fell briefly quiet. He demonstrated an ability to bring science to the public as he spoke to the media regarding her antics. He was an amazing man, a hell of a geologist, and he'll never be forgotten: not just because he died on the mountain that day, but because he was so very good at what he did.

_cropped.jpg/800px-Dave_Johnston_collecting_sample_from_Mount_St._Helens_crater_lake%2C_30_April_1980_(USGS)_cropped.jpg)

Astonishing. Heart-breaking.

ReplyDeleteI just read that Harry Glicken, whose place Johnston took at Mount St Helens, was killed eleven years later in an eruption of Mount Unzen, in Japan. Irony or destiny?

ReplyDeleteI don't think Glicken ever recovered from the death of Johnston. I came across an article that claimed he saw Mt. St. Helens erupting as he was in the car on his way to his meeting with his advisor. He suffered from intense survivor's guilt. I think he threw himself into his work afterwards - completely understandably - and perhaps even wanted to keep putting himself in harm's way.

DeleteBoth were brilliant scientists who helped many people and certainly saved lives. Modern heroes.

Wow!

DeleteI've always felt for a geologist to become geology is to attain the highest possible goal.

ReplyDeleteA la Pompeii?

DeleteMartin's recording is here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1fBxCrglvts

ReplyDeleteGlicken's work documenting the post-eruption hummocks is a touching tribute to his mentor. I've I hiked the area and it is incredible.

ReplyDeleteHi.. What is your source for this story? I don’t find this anywhere when looking to cross reference this

ReplyDelete