I am on a business trip out-of-state now, and will be away until mid-February. I will try to get some posts up while I am away.

I was just contacted by a Japanese researcher who's looking into the Setagaya murders. The internet is such an amazing place! We'll be talking, and I look forward to sharing whatever I learn with you.

Monday, January 25, 2016

Thursday, January 7, 2016

Vancouver, Vancouver, This Is It!: The eruption of Mount St. Helens

David A. Johnston never expected to be famous. He was a vulcanologist, after all. While important, it's rarely a newsworthy career.

Sadly, David was an exception.

David completely his undergraduate work in geology at the University of Illinois, and followed up with his master's and doctorate work at the University of Wisconsin. In 1979, the 29-year-old joined the United States Geologic Survey, or USGS. Johnston's specialty was in gas sampling. He hoped it would allow scientists to identify hazards before they violently erupted.

Johnston's work took him across the Pacific Northwest, and he was at his alma mater, the University of Wisconsin, when Mount Saint Helens woke herself from her 123-year rest with a shudder.

The first earthquakes struck on March 15th, 1980. Intrigued, Johnston contacted his mentor, Stephen Malone, who immediately allowed him to escort reporters to the area. Johnston was the first geologist on the scene and remained a leader of the team studying the mountain.

By March 24th, the vulcanologists were confident that the earthquakes were the precursor to an eruption. On the 26th, a phreatic, or steam, eruption burst forth from the mountain.

On April 17th, a bulge appeared on the north side of the mountain. Concerns arose that this could become a lateral blast, which is exactly what it sounds like: a blast erupting from the side, and not the top, of a volcano.

This series of photos from Scientific American shows the growth of Mt. St. Helen's "ominous bulge":

It seems surprising in retrospect, but Johnston was one of few people to share this opinion. Though it was obvious the mountain was close to erupting, the questions of where - and when - remained a mystery.

Governor Dixy Lee Ray declared a state of emergency on April 3rd, and by the 30th, a "red zone" was declared around the volcano, allowing only people with a special pass to climb the mountain.

By this point, Johnston was downright scared of the volcano. It was ready to pop at any minute. It was incredibly dangerous to be anywhere on the slopes of St. Helens.

And then the volcano went silent.

The phreatic activity slowed. Between May 10th and May 15th, the only change in the mountain was the growth of that looming bulge. On the 16th, the phreatic eruptions stopped completely.

At this time, Johnston was mentoring a student, Harry Glicken.

Glicken bumped into Johnston in the hallways of USGS and asked if he would take his place on May 18th.

Johnston was extremely reluctant. He had issued the most forceful warning to the public to stay away from the mountain, and had been scolded by his superiors for it.

"I don't like this at all," a newspaper quotes him as saying. "I'm not trying to be an alarmist, and I'm usually pretty calm around volcanoes, but I'm genuinely afraid of this thing... I think it would be wise to get out of here."

Seconds later, the signal from his radio was gone - and so was David.

Amateur HAM radio operator Gerry Martin saw the blast as well. He broadcast, "Gentlemen, the uh... camper and the car sitting over to the south of me is covered. It's gonna get me, too. I can't get out of here..."

Then his signal went silent, as well.

A recording does exist of Martin's message, but I can't seem to locate it at this time. Please contact me if you find it!

Robert Landsburg, a local photographer, already had his camera on a tripod. As the mountain burst forth its fury, he pumped out four photos, unwound the film, and threw it into his backpack. He then dove on top of the backpack to protect its contents.

His pictures survived.

Glicken was devastated and guilt-stricken. He convinced three separate helicopter pilots to fly over the mountain, but there was no sign of the trailer or his mentor - they had completely vanished.

Don Swanson found Johnston's parka and backpack.

It wasn't until 1993 that the trailer from Coldwater II was recovered, but the body of David Johnston was never found.

A touching tribute to Johnston and the other scientists who perished that day is located here:

Sadly, David was an exception.

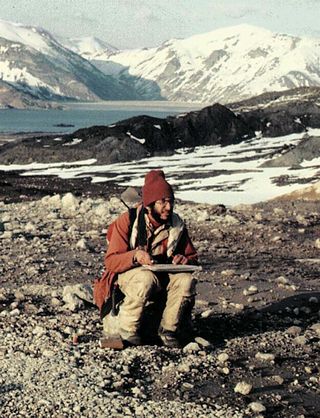

The iconic image of David A. Johnston at Coldwater II.

David completely his undergraduate work in geology at the University of Illinois, and followed up with his master's and doctorate work at the University of Wisconsin. In 1979, the 29-year-old joined the United States Geologic Survey, or USGS. Johnston's specialty was in gas sampling. He hoped it would allow scientists to identify hazards before they violently erupted.

Johnston's work took him across the Pacific Northwest, and he was at his alma mater, the University of Wisconsin, when Mount Saint Helens woke herself from her 123-year rest with a shudder.

The first earthquakes struck on March 15th, 1980. Intrigued, Johnston contacted his mentor, Stephen Malone, who immediately allowed him to escort reporters to the area. Johnston was the first geologist on the scene and remained a leader of the team studying the mountain.

By March 24th, the vulcanologists were confident that the earthquakes were the precursor to an eruption. On the 26th, a phreatic, or steam, eruption burst forth from the mountain.

This phreatic eruption took place on the 30th.

On April 17th, a bulge appeared on the north side of the mountain. Concerns arose that this could become a lateral blast, which is exactly what it sounds like: a blast erupting from the side, and not the top, of a volcano.

This series of photos from Scientific American shows the growth of Mt. St. Helen's "ominous bulge":

It seems surprising in retrospect, but Johnston was one of few people to share this opinion. Though it was obvious the mountain was close to erupting, the questions of where - and when - remained a mystery.

Governor Dixy Lee Ray declared a state of emergency on April 3rd, and by the 30th, a "red zone" was declared around the volcano, allowing only people with a special pass to climb the mountain.

David Johnston takes a sample from the mountain's crater lake, April 30, 1980.

Despite the bulge, which was growing at the rate of 5 to 9 feet per day, the north side of the volcano still wasn't producing much vent activity.

This is a vent, or fumarole.

Wrongly assuming that this meant an eruption was further off than they thought, the USGS instead warned residents about the potentiality of landslides from the north face. Johnston was the one who issued the warning to the press.

By this point, Johnston was downright scared of the volcano. It was ready to pop at any minute. It was incredibly dangerous to be anywhere on the slopes of St. Helens.

And then the volcano went silent.

The phreatic activity slowed. Between May 10th and May 15th, the only change in the mountain was the growth of that looming bulge. On the 16th, the phreatic eruptions stopped completely.

At this time, Johnston was mentoring a student, Harry Glicken.

Harry Glicken

Glicken had been monitoring the Coldwater II station, using laser ranging to track the growth of the bulging mountain. After working six days straight in the tiny trailer, Glicken needed a day off to visit with his professor for his graduate work at the University of California. He was supposed to be relieved by geologist Don Swanson. Swanson, however, wanted to meet with a graduate student who was returning to Germany the next day.

Glicken bumped into Johnston in the hallways of USGS and asked if he would take his place on May 18th.

Johnston was extremely reluctant. He had issued the most forceful warning to the public to stay away from the mountain, and had been scolded by his superiors for it.

"I don't like this at all," a newspaper quotes him as saying. "I'm not trying to be an alarmist, and I'm usually pretty calm around volcanoes, but I'm genuinely afraid of this thing... I think it would be wise to get out of here."

After heavy hesitation, he accepted the job of the post at Coldwater II. It was six miles away from the bulging north face, after all. Surely whatever happened on the mountain wouldn't reach him.

Just before he left, Glicken snapped the photo of his mentor in front of the tiny trailer, notebook in hand, grinning at the camera.

At 8:23am in the morning of May 18th, Mt. Saint Helens erupted.

David must have dove towards the radio. He screamed his last words into the microphone.

"Vancouver, Vancouver, this is it!"

Amateur HAM radio operator Gerry Martin saw the blast as well. He broadcast, "Gentlemen, the uh... camper and the car sitting over to the south of me is covered. It's gonna get me, too. I can't get out of here..."

Then his signal went silent, as well.

A recording does exist of Martin's message, but I can't seem to locate it at this time. Please contact me if you find it!

Robert Landsburg, a local photographer, already had his camera on a tripod. As the mountain burst forth its fury, he pumped out four photos, unwound the film, and threw it into his backpack. He then dove on top of the backpack to protect its contents.

His pictures survived.

Glicken was devastated and guilt-stricken. He convinced three separate helicopter pilots to fly over the mountain, but there was no sign of the trailer or his mentor - they had completely vanished.

Don Swanson found Johnston's parka and backpack.

It wasn't until 1993 that the trailer from Coldwater II was recovered, but the body of David Johnston was never found.

A touching tribute to Johnston and the other scientists who perished that day is located here:

I will admit this: I cry. Every time. Every time I catch sight of the geologist he was, and realize anew what we lost that day, I tear up. He furthered our knowledge; he saved lives by being one of the voices saying that St. Helens was still dangerous even when she fell briefly quiet. He demonstrated an ability to bring science to the public as he spoke to the media regarding her antics. He was an amazing man, a hell of a geologist, and he'll never be forgotten: not just because he died on the mountain that day, but because he was so very good at what he did.

The Trial of the Century 5: The Case Against Hauptmann and Other Tidbits

Tidbits and clarifications. Unless otherwise noted, this comes from Hauptmann’s Ladder by Richard T. Cahill, Jr.

On to it:

1) Origins of the rumors of Little Lindy’s supposed deformities.

The Lindberghs always strived to keep their private lives private - unsuccessfully. They were, understandably, very secretive about their first son, as they believed the constant media exposure wasn’t good for him.

Sadly, this secrecy led to rumors that little Charles was being kept from the public eye because he was deformed and the Lindberghs were embarrassed. Cahill testily notes, “It never occurred to the reporters that they were the real reason for the Lindberghs’ overprotectiveness of their child.”

At one point, the rumors were so out-of-control that Lindbergh called a press conference to address them, specifically denying five newspaper chains from attendance due to their publishing stories claiming his son was deformed. He chided the media for their constant coverage and asked that they back off.

The only “deformity” little Lindy had was overlapping toes on his right foot, which was used in the identification of the corpse. There is absolutely no evidence that there was anything else wrong with the child.

2. Lindbergh’s day before he arrived home.

“Charles spent the day in New York visiting the offices of Pan American Airways, Transcontinental Air Transport, Inc., and the Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research, as well as his dentist.” Cahill cites Kidnap by George Waller here. “Charles had been scheduled to appear at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel as a guest of honor for a dinner held by NYU. Due to a scheduling error, Lindbergh failed to attend the dinner and came home instead. This innocent error has been used by authors of a tabloid-style book to support a theory that Lindbergh actually killed his own son…” referring to Ahlgren and Monier’s Crime of the Century: the Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax.

It seems that Charles’ day is quite well accounted-for.

3. The ladder

The ladder was actually quite ingeniously constructed. It was made of three pieces, the first two of which folded together on hinges, and the third was separate, to be connected via a wooden dowel pin, which was also left at the scene. The three pieces fit together perfectly (as I showed you in the pictures from the museum yesterday), so that it would fit in the back of a car. It was made of lightweight wood and weighed only 38lbs. The rungs were spaced so that there only exactly as many as were needed to climb the ladder, to make it lightweight. It was designed specifically for a certain person to use. However, the kidnapped underestimated the weight of the baby, and the ladder broke.

4. The kidnapper also left a chisel at the scene, probably to open locked shutters - but he didn’t wind up needing it, since the nursery shutters on the window he used were warped and would not close properly. It was a ¾ inch wood chisel. The same chisel was found missing from Hauptmann’s tools in his garage. While a ¾ inch metal chisel was found, that’s not the same thing - it has a different angle and is used for working with metal.

In total, he left behind the ladder, the wooden dowel to connect the two pieces, and the wood chisel. The thumb guard was left in the driveway of Highfields, probably when he ripped Charles' sleeping-suit off his body. At the scene of the baby's shallow grave, he left behind a burlap sack he had stuffed the baby into (traces of the baby's hair were found in the sack).

5. Hauptmann’s finances - there is no ransom money unaccounted for

From the testimony of William Frank, an investigator with the US Treasury Dept.:

On April 2, 1932, the day the ransom was paid, the Hauptmanns had $4,941.40 in total assets.

On September 19, 1934, the day Bruno Richard Hauptmann was arrested, they had $56,059.65. This includes all expenditures, income, and ransom money hidden in Bruno’s garage.

When you subtract $4,941.40 from that amount, as well as the known income the Hauptmanns received, you have $49,950.44 left unaccounted for - just .56 less than the ransom paid.

While Hauptmann did trade on the stock market, he lost more than he won, and actually lost $5,728.63 during that time period.

No ransom money was spent after Hauptmann was arrested.

6. Hauptmann’s employment records

Edward Morton testified about this, and entered the employment records of Reliance Property Management, the company that handled Majestic’s payroll, into evidence. Hauptmann started working for Majestic Apartments on March 21st - not March 1st, the day of the kidnapping - and finished on April 2, 1932, the day the ransom was paid.

7. Hauptmann’s alibi witnesses

This is a big one I had wanted to find out about.

From The Lindbergh Case by Jim Fisher

Anna claimed that Bruno had arrived at the bakery where she waitressed at 7pm on March 1st, and waited around until she finished her shift at 9:30, then drove back to their apartment. However, on cross, she was reminded that in October 1934, “when Insp. Henry Bruckman of the Bronx had asked her if she could recall what her husband had been doing on March 1, 1932, she said that she couldn’t remember what he was doing on that particular day.” Anna admitted that she had said that. Anna was also forced to admit that she could reach the top shelf of her closet where Bruno said he had placed the shoebox full of money, that she dusted and cleaned it, and had never seen the shoebox there.

The next witness was Elvert Carlstrom, who said he’d been in the bakery at 8:30pm on March 1st and had seen Hauptmann there. On cross, he was asked to describe Hauptmann. He tried to look at Hauptmann, and when his view was blocked, was unable to provide a description.

After a recess, he was asked what else he did that night. The witness eventually plead the 5th. The next day, prosecution returned with information that Carlston was a petty thief, bootlegger, and mentally unstable.

The next witness was another customer at the bakery, Louis Kiss, who said Hauptmann had come in that night accompanied by “a police dog,” which I’m assuming is a German shepherd or something. The Hauptmanns did walk a neighbor’s dog. He said he remembered the day because a week earlier his son had to go to the ER. However, that year had been a leap year so the timing was off. Cross discovered he was a bootlegger and a drunk.

The next witness gave his name as August Van Henke, who said he’d seen Hauptmann at a gas station near the bakery, and spoke with him as Hauptmann had “a police dog” and his dog, who looked similar, was missing. The dog was not his. Cross discovered that the witness went by two other names- August Wunstorf and August Markhenke - and the restaurant he owned was actually a speakeasy. He may also have run a brothel.

The next witness, Lou Harding, said he saw a blue car on March 1st in Trenton, which pulled up and asked for directions to the Lindbergh estate. He said he saw a ladder in the backseat. He said he reported the incident to Princeton police, who took him to Highfields, where he was questioned by two detectives and showed him the ladder which he identified as the one he saw.

On cross, he admitted to serving time in Rahway prison, and had also been convicted of assault and battery, and on another occasion, carnal abuse. He had also served two sentences for drunk-and-disorderly at the Mercer County Workhouse. The detective who he claimed questioned him had never worked on the Lindbergh case. He also couldn’t describe the ladder.

And that was it for Hauptmann’s alibi witnesses.

Bonus Round: Violet Sharp

This information comes from Their Fifteen Minutes by Mark Falzini. I found it very interesting and haven’t seen it mentioned elsewhere.

“According to Emily, Violet Sharp’s sister, Violet told her on a couple of occasions that she had been married years before in London, when she was just 17 years old. She said his name was George Payne. When asked about this after Violet’s suicide he denied it and there was no record of the marriage ever found. Emily said it had only been mentioned ‘in passing’ and their mother, Lucy, first told her of it… Violet allegedly kept the marriage secret from their mother, ‘...until he was supposed to be dead. My mother said, ‘I don’t believe it’ to which Violet retorted, ‘Fine, it didn’t happen then!’’

“The alleged marriage came to light in 1929 when Violet applied for her passport. Her application was delayed because she needed to have letters of recommendation from her previous employers and some of them were addressed to Violet Payne…

“After her suicide, Scotland Yard was asked to investigate the alleged marriage, but they found no record of it at Somerset House in London. They did learn that although Violet said that he had died, George Payne was very much alive and living in London. They paid him a visit at his home…

“...He married Ellen Cone in 1896 and they had one daughter, Winifred Annie who was born shortly thereafter...

“George Payne was a printer’s stock keeper and in early 1927 he met Violet when they both worked for Mr. Pearce-Leigh in Gloucester Square, Paddington. Payne was employed as a butler and Violet as a parlor maid. They worked there for six months, until the Pearce-Leighs moved to a country home.

“George stated that he and Violet were never intimate; at most they went to the movies together. After leaving the Pearce-Leighs employ they never worked together again. Violet would write him and they would meet for walks whenever she got back to London. George set up an address for the letters… because he did not want them going to his home. “

Falzini speculates that Sharpe’s record of mental instability may have exacerbated the extent of the police questioning in her mind, making them seem more intense than they actually were. She did not make things any easier for herself by lying to police (more on this later). He wonders, “Was her close friendship with George Payne just that, a friendship but one magnified and distorted by Violet to the point that she actually believed they had been married? Why would she tell her employers that she was Mrs. Payne instead of Miss Sharp?”

Wednesday, January 6, 2016

It's that time of year...

I apologize for the lack of updates lately. Things have been in an upheaval. I'm in the middle of a chaotic move as well as a change of career, and of course, the holidays came smack dab in the middle of everything!

First of all, exciting news: my article is now up on Listverse! I'm so glad one of my favorite websites to read is just as pleasant to work with, and I look forward to contributing more to their site.

I had some free time this week, and finally made the trip over to the New Jersey State Police museum to view their Lindbergh exhibit. For now, you can view an Imgur album here. I've made arrangements to view the State Police archives shortly. I also made my way to view the trial transcripts again, and plowed through a ton of research that I'll be sharing with you soon.

Thank you for your patience! This new year will bring lots of new, exciting research!

First of all, exciting news: my article is now up on Listverse! I'm so glad one of my favorite websites to read is just as pleasant to work with, and I look forward to contributing more to their site.

I had some free time this week, and finally made the trip over to the New Jersey State Police museum to view their Lindbergh exhibit. For now, you can view an Imgur album here. I've made arrangements to view the State Police archives shortly. I also made my way to view the trial transcripts again, and plowed through a ton of research that I'll be sharing with you soon.

Thank you for your patience! This new year will bring lots of new, exciting research!

Tuesday, January 5, 2016

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

_cropped.jpg/800px-Dave_Johnston_collecting_sample_from_Mount_St._Helens_crater_lake%2C_30_April_1980_(USGS)_cropped.jpg)